Today's Out Spotlight is a partnership in both love and work. Between them they have made 47 films and received six BAFTAS and six Academy Awards. Their partnership has it's own place

in the Guinness Book of World Records for the longest partnership in independent cinema history. Today's Out Spotlight is producer Ismail Merchant and director Jame Ivory.

Coming from worlds apart they found a partnership both on screen and off that lasted 44 years.

Born Ismail Noormohamed Abdul Rehman in Bombay, December 25 1936, Ismail Merchant was the son of Hazra and Noormohamed Haji Abdul Rehman. His father was a Mumbai Memon textile dealer. Growing up he spoke both Gujarati and Urdu at home, and learned Arabic and English at school. At the age of 11, his family was caught up in the 1947 partitioning of India, his father, president of the Muslim League, refused to move to Pakistan. Merchant later said that he carried the memories of the "butchery and riots" of the time into adulthood.

Merchant attended St. Xavier's College, Bombay (Mumbai) and it was there that he developed his love of film.

After graduation from St. Xavier's he traveled to the US to study at New York University, where he earned a MBA. While at NYU he supported himself by working as a messenger for the United Nations and used the opportunity to persuade Indian delegates to fund his film project. On the job training for a producer. He said of the time , "I was not intimidated by anyone or anything".

James Francis Ivory was born born June 7, 1928 in Berkeley, California, the son of Hallie Millicent and Edward Patrick Ivory, a sawmill operator and grew up in Klamath Falls, Oregon. Ivory was a film fan from a early age, but not of the films he would become famous for, but for disaster movies. He came to movie making later, first attending the University of Oregon, majoring in Architecture and Fine Arts and then pursuing film studies at the University of Southern California School of Cinematic Arts, where he directed his short film

Four in the Morning in 1953.

Then he wrote, photographed, and produced Venice: Theme and Variations a half-hour documentary submitted as a thesis film for his degree in cinema at USC. The film was named by The New York Times in 1957 as one of the ten best non-theatrical films of the year. He graduated from USC in 1957

Ivory came to New York that year, and it was there, in 1961, that he met Merchant, at a screening of Ivory’s second film, a short documentary based on Indian miniatures, entitled

The Sword and the Flute. Merchant introduced himself: they had a friend in common in the actor Saeed Jaffrey. He wanted to make films set in India for an international market, and in Ivory he found his collaborator and much more. Merchant completely disregarded Ivory’s inexperience directing actors, immediately began raising money for their first feature film together.

Later in 1961 they formed Merchant Ivory Productions. For the next 44 years, Merchant Ivory Productions produced 47 films. Their first film would be an adaptation of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s novel

The Householder. Jhabvala became the screenwriter for most of their productions. Some of their titles include The Bostonians, A Room with a View, Maurice, Mr & Mrs. Bridge, and Howard's End.

In 1961, Merchant made a short film, The Creation of Woman. It was shown at the Cannes Film Festival and received an Academy Award nomination.

In 1963, MIP premiered its first production, The Householder. It was the first Indian-made film to be distributed internationally by a major American studio, Columbia Pictures. But it wasn't until the 1970s that their partnership "hit on a successful formula for studied, slow-moving pieces. Merchant Ivory became known for their attention to period detail and the opulence of their sets". Their first success in this style was The Europeans.

Merchant Ivory had produced such films as A Room with a View, Maurice, Howard's End, Remains of the Day, Mr. & Mrs. Bridge, Jefferson in Paris,Surviving Picasso,The Golden Bowl, Le Divorce, The White Countess, and The City of Your Final Destination.

Merchant also directed in addition to producing. He directed a number of movies and two television features. For television, he directed a short feature entitled Mahatma and the Mad Boy, and a full-length television feature, The Courtesans of Bombay made for Britain's Channel Four. He made his film directorial debut with 1993's In Custody based on a novel by Anita Desai, and starring Bollywood actor Shashi Kapoor. Filmed in Bhopal, India, it won National Awards from the Government of India for Best Production Design and special award for the lead actor Shashi Kapoor. His second directing feature, "The Proprietor," starred Jeanne Moreau, Sean Young, Jean-Pierre Aumont and Christopher Cazenove and was filmed on location in Paris.

Of his partnership with Ivory and Jhabvala, Merchant once commented: "It is a strange marriage we have at Merchant Ivory . . . I am an Indian Muslim, Ruth is a German Jew, and Jim is a Protestant American. Someone once described us as a three-headed god. Maybe they should have called us a three-headed monster!"

Merchant was well known for his "lavish private parties" and for cooking for the cast of MIP productions. He was fond of cooking, and he wrote several books on the art including Ismail Merchant's Indian Cuisine; Ismail Merchant's Florence; Ismail Merchant's Passionate Meals and Ismail Merchant's Paris: Filming and Feasting in France.

He also wrote books on film-making, including a book about the making of the film The Deceivers in 1988 called

Hullabaloo in Old Jeypur, and another about the making of The Proprietor called

Once Upon a Time . . . The Proprietor. His last book was entitled,

My Passage From India: A Filmmaker's Journey from Bombay to Hollywood and Beyond.

In 2002, Merchant was awarded the Padma Bhushan,the third highest civilian award in the Republic of India. He was also a recipient of The International Center in New York's Award of Excellence.

Merchant died in Westminster, London, on May 25, 2005, at age 68, following surgery for abdominal ulcers. It was in the middle of filming " The White Countess". They had come to do further shooting in London. He was buried in the Bada Kabrestan in Marine Lines, Mumbai, on May 28th, in keeping with his wish to be laid to rest with his ancestors.

Ivory grief stricken and threw himself into work. “I was badly shaken — that’s an understatement. But I knew we had to finish what we’d started The White Countess. He had also already begun work on

The City of Your Final Destination. “I was overwhelmed with grief but I had to do it and I’m glad I did. It went on for months and months and months, but after we’d done the film I was in a better frame of mind."

Although relatively quiet about their relationship they were a true partnership on and off screen. Speaking after Merchant's death, Ivory was asked about his life had been since losing his partner. He adeptly spoke about in terms of their professional relationship, telling how difficult it is to make a film without his longtime partner. Each had strengths in their film making and areas where they deferred to the other. “The one thing I knew not to do — which I could not help doing — was to interfere in his financial arrangements. If there was some woebegone person who was working for us on a film, they’d come to me and say: ‘I’m only being paid $100 a week,’ or something. I’d go to Ismail and say: ‘So-and-so is being underpaid and it’s not fair.’ Maybe he’d believe that, and see they got a raise, but he’d rant and rave that I was getting in his hair. We had terrible fights about that.”

But Merchant could take the lead sometimes in the partnership, hurrying Ivory into a project he wasn’t that interested in. “That was the case with

A Room with a View. We had paid for the rights and it was just sitting there. But Ruth Jhabvala and I were working on another screenplay and I said things like, ‘Oh, must we? I don’t want to do another period film right now.’ But we did it and thank God we did!”

And Merchant could be masterful taking care of things and then presenting it completed for Ivory. “He cast some big parts in the films without telling me — except they were people like James Mason and Maggie Smith. So who could complain?

For a couple who was quiet about their relationship, many wondered what motivated them to adapt E. M. Forster’s novel

Maurice. “I just wanted to make it,” Ivory says. “I wasn’t making it for some self-revelatory reason. We didn’t really know what would happen when the film came out. And it turned out that its release coincided with the worst period of the AIDS crisis — people were being mowed down right and left. I think that discouraged the press from being censorious about it, and it was well-received, particularly here. (in the US) But it was curious that in England it was not so well received, and not well received by the gay critics — one knew who they were. They just couldn’t embrace it for what it was: a gay story with a happy ending. They didn’t want to be associated with it. I thought that was a remarkable example of hypocrisy in the press.”

Ivory continues to work with Merchant Ivory productions even after the passing of his beloved Ismail.

Merchant Ivory Productions

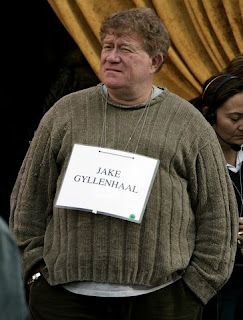

Jakey, you don't say. This reminds you of your dress from SNL?

Jakey, you don't say. This reminds you of your dress from SNL?  Jakey, you don't say. This reminds you of your dress from SNL?

Jakey, you don't say. This reminds you of your dress from SNL?  So do you use a two in one shampoo and conditioner to get

So do you use a two in one shampoo and conditioner to get Mary you have the best legs in Hollywood.

Mary you have the best legs in Hollywood.